Land navigation is one of those courses where students can level up in an extremely short time. It’s one of my favorite courses to instruct, and I just wrapped up teaching a class of 12 a couple of days ago. When the course starts, I ask students their understanding of land navigation on a scale from 1-10. No student commented with a number over 4.5; most were 1s or 2s. Not knowing how to use tools like a topographic map, UTM corner, Suunto M3 compass, or even their pacing as a physical metric is no shame. Our land navigation class stresses the importance of learning to “speak navigation” to communicate more effectively. On the whiteboard in the front of the room, I usually write “Position, Direction, and Distance,” as these are the foundation of basic navigation. Just like Google Maps or Waze, only a few elements are needed to get a person from one point to another. Here’s a brief explanation of those and how they’re determined.

Position

Humans take comfort in location. Don’t believe me? Consider what happens when we are lost or turned around. When that happens, our stress level rises, and we may sweat or have an elevated heart rate. For land navigation, you must identify positions on a map, and the tools we can use are terrain association, taking references from the physical surroundings, or UTM protractors to convert our understanding of where we are to numbers we can share with others. UTM corners like https://fieldcraftsurvival.com/pocket-sized-utm-corner-ruler/, the one we sell at Fieldcraft can help you make sense of 1000x1000 meter grid squares. We harp on students learning how to use these tools, and by the end of the course, the students will be able to provide a grid down to an accuracy of 10 meters. These numbers can be relayed to a second party and plotted on a map like the game of Battleship, only grown up. Like navigation systems in your car that provide moments to turn, continue straight, and eventually stop, you use various UTM (or MGRS if that’s your preference) to mark key points to take further action.

Direction

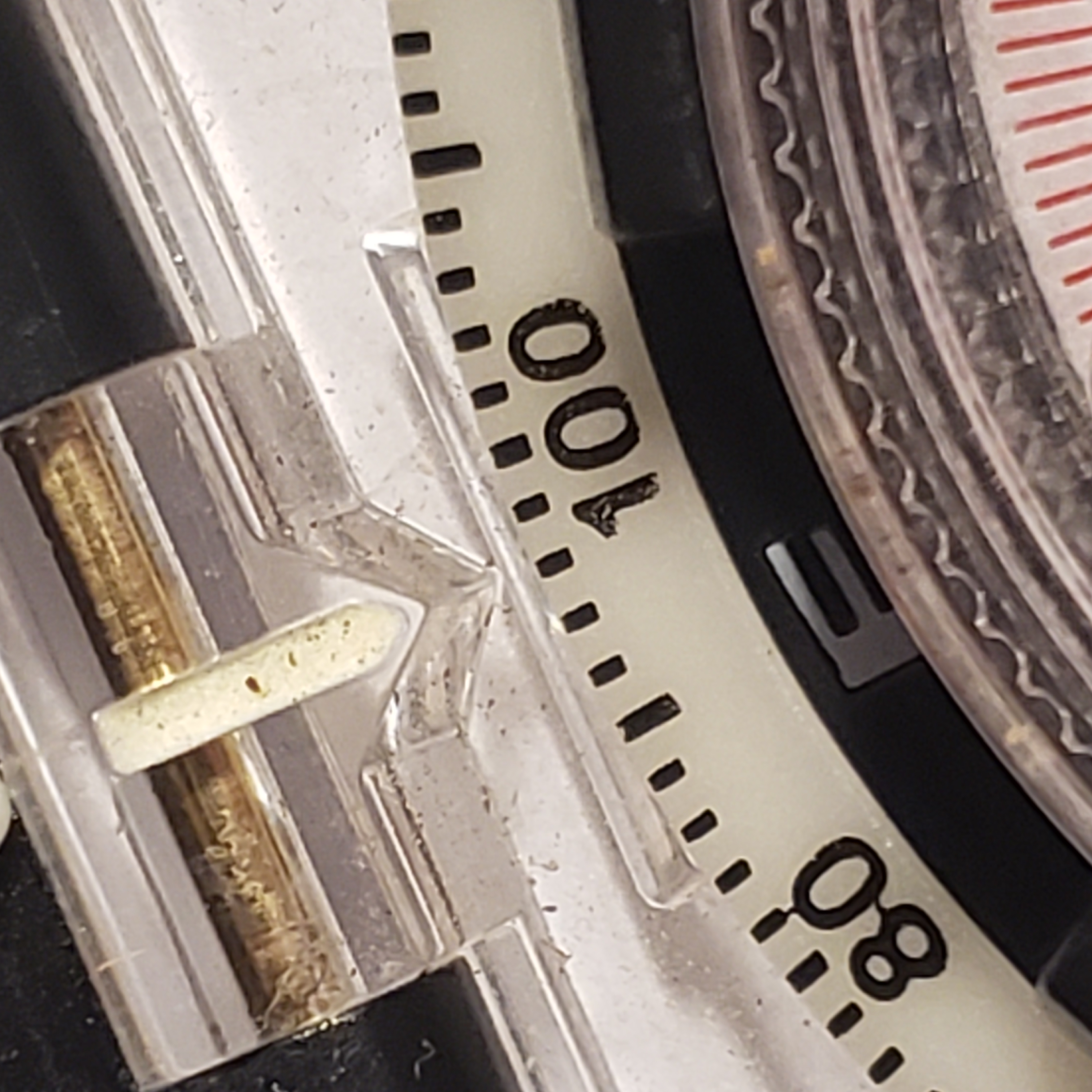

Unlike driving in a car where you can follow the road at key points, there may not be a trail or a road when you travel overland. In land navigation, instead of using asphalt as your reference, you use degrees off grid north lines to determine the direction you will move out. Note I stated “grid north” and not magnetic north. Eventually, you must adjust your compass’s declination to make your map and compass speak the same language or do simple math, adding or subtracting the difference between grid north and magnetic north. Finding direction isn’t difficult with a good map and compass. Each grid line represents 0 degrees north, and you can measure the degrees off of the grid north with either your UTM protractor or your compass. Ideally, you use a good baseplate compass with reference lines etched inside the bezel to line up with parallel lines on your map. Either way, the degree you read on your map will help you determine the direction you must dial and follow in the great outdoors. At that point, and with a good compass, you can move in a particular direction instead of just a general direction like “easterly’ or “northerly.”

Distance

Unless you are walking to a specific point on a map with a clear catch feature, you must identify the distance between points. Distance can be measured on the map using the string, paper, or ruler method, and over land, it is measured with pacing or tracking time. Humans aren’t equipped with odometers like vehicles, meaning we have to rely on less accurate means of measurement. That said, in the recent course we ran here at Fieldcraft, most of my students were within 2 percent of the distance I measured over hundreds of yards. What is interesting about pacing and how it factors into the position, direction, and distance formula is that it allows you to estimate how many paces you’ll need to take along a particular leg of a route. As you write out a route card for travel through the woods, the dialogue you should be able to provide to someone over a radio, text message, or note could sound like, “when you reach 17S PU 12345 67890, turn to 120 degrees South East and travel 2/10th of a mile or 188 paces”. If this sounds foreign to you, I encourage you to take the time to learn how to navigate.

Land nav skills are vital for movement in the woods. If you’re wondering what true Fieldcraft is, it’s having the ability to shoot, move, communicate, and resupply/support. If you can’t land nav, you won’t know how to move into position and may not be able to communicate movement details to your support team. It’s easy to say, “I don’t get lost,” or “I know these woods like the back of my hand,” but even the most experienced get lost, and you may not be in your woods. Hunters, scouts, nature enthusiasts, minutemen, etc, will be better served by understanding how to move about in the woods. For those doubling down on buying more gear and not backing that gear up with mental software, I’d encourage you otherwise. Knowing how to navigate with a map and compass gives you a new appreciation for how GPS units work, and you’ll understand how to ration the battery use and use it only to verify the position on your map. Land navigation is a perishable skill, and there is a lot to learn, but you can start by learning how to determine these primary three: position, direction, and distance.

Click the training tab on our website to find a Land Navigation near you in 2024, or join us at one of these upcoming courses:

Aberdeen, NC 1/6/2024 / Lexignton, SC 2/24/2024 / Centennial, CO 3/2/2024 / Provo, UT 3/2/2024